A decade ago, while he was in jail for acts of civil disobedience involving an oil rig in the Greenlandic Arctic, climate activist Kumi Naidoo, then executive director of Greenpeace International, had a revelation: “If they can use the law against us, we can use the law against them,” he told his colleagues.

At the time, the global environmental group with a hankering for nonviolent confrontation had a six-person legal department, focused mostly on its fleet of ships, defending against court actions, and getting people like Naidoo out of jail. He began wondering whether the law might also be deployed in “affirmative, offensive strategies to achieve our goals.” Why couldn’t climate activists “do to the fossil-fuel industry what the anti-tobacco lobby did to the tobacco industry?” Greenpeace branched out into filing actions, not just taking them.

Ka Hsaw Wa, an activist in Burma (Myanmar), had a similar revelation in 1994, during a conversation he witnessed between a student activist and a U.S. law student working as a summer intern for a human rights group. The student activist, dismayed by the ongoing brutal repression surrounding the laying of a gas pipeline, said: “We’ve done everything else, and they still ignore us, and our people keep suffering. Why would it be illegal if we just blew up the pipeline?”

The law student, Katie Redford, replied, “We can blow the pipeline up, by using the law itself as our weapon.”

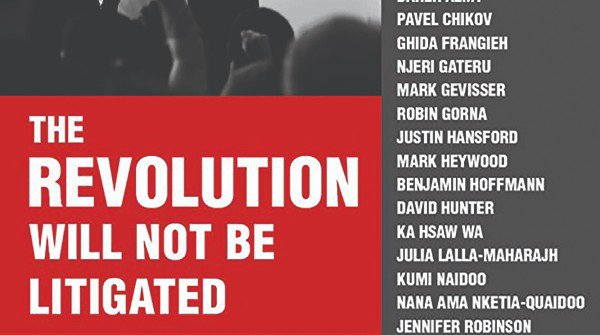

These are some of the many stories and conversations told in the new book The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated, co-edited by Redford, who went on to head EarthRights International and the Equation Campaign, and South African journalist and author Mark Gevisser. The collection brings together more than two dozen contributors from around the world to reflect on various aspects of the role of lawyers and the law in fighting for social justice. Most wrote short essays; a few were interviewed.

Actor and activist Jane Fonda, in the book’s foreword, hails its contributors as “all doers, people who have acted bravely to change the world. But they have come to understand, as I have, how public advocacy is nine-tenths of any struggle—and that storytelling is what drives any public advocacy campaign.” The book’s recurring credo, cited by Fonda, is that “it takes a lawyer, an activist, and a storyteller to change the world.”

In reading The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated, Fonda relates, “I learned much about the power—but also the limitations—of such strategic litigation.” First, legal action is “often only a means to an end, which is the advancement of your cause. Even if you lose the case you can ‘win’ in a court of public opinion, or in the way you have brought people together to take action.” Secondly, the power of law depends on the power of people: “If you are seeking transformational change, a legal strategy must go hand in hand with a movement-building strategy.”

This is a constantly recurring theme in The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated. The book’s very title, a riff on the Gil Scott-Heron song “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised,” conveys this tension. Yes, litigation can and often does lead to significant change. But the law alone cannot change the world.

“The message of this book is clear,” Redford writes, by way of summing things up. “The law is important; more than that, it has the power to be transformational. But the revolution will not be litigated. It will be fought by those with the most at stake, with the help of the law in service of the movement.”

Readers of The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated will meet lawyers working on a wide array of causes, from holding multinational companies accountable for complicity in human rights violations and harm to the Earth; to opposing police brutality and discriminatory practices; to defending protesters at Standing Rock and Ferguson; to opposing anti-LGBTQ+ repression in Kenya and female genital cutting throughout Africa; to protecting WikiLeaks publisher Julian Assange; to fighting for AIDS treatment in South Africa, reproductive rights in Ireland and Poland, and the decriminalization of sex work in Kenya.

For some people, the idea that the law can be used to the advantage of ordinary people is a hard sell. Government and corporations have long used it as an instrument of injustice, to enforce the dominion of the haves over the have-nots.

“The law,” notes Mark Heywood, an activist in South Africa, “is not a natural ally of the downtrodden. It is clipped, clinical, and precise, logical and formulaic.” It can be used “as a check on power as well as a means for resolving disputes.” Societies with laws meant to protect rights are better off than those without them. “Yet on its own, it cares nothing for democracy or rights.”

Societies with laws meant to protect rights are better off than those without them. “Yet on its own,” notes one essayist, the law “cares nothing for democracy or rights.”

And then there is the reality that even when you win a fight in the courts, the immediate impact may be minimal, if there is any at all. Redford and Gevisser both write about their years-long fight to get the U.S. Supreme Court to rule, as it did in 2019, that the World Bank was not immune from being sued for the damage caused by its lending decisions. The case, Jam v. International Finance Corporation, was a huge win for the plaintiffs—fishermen from the Gulf of Kutch in western India who had been harmed by a World Bank-funded power project. But, Gevisser notes, in terms of the lives of the people involved, including the lead plaintiff, an elderly fisherman named Budha Ismail Jam, nothing had changed.

“I had been working with him for eight years already, but we had only just won the right to begin fighting the World Bank on its own turf!” Gevisser writes. “It would be a long time, still, before Mr. Jam felt any kind of tangible relief.”

In the lawsuit filed over the Burmese pipeline, a decision was made to settle rather than let the case play out in court. Afterward, wrote Ka Hsaw Wa in his essay, “the practice on the ground changed” and the human rights situation in Burma “improved significantly.” This was, he mused, “because the corporations know people are watching now, and if the corporations care, so do the generals that profit from their operations. After our case, there were fewer violations; this gave the villagers hope.”

In fact, Ka Hsaw Wa writes, “I’ve come to a different definition of what it means to win. My definition of winning is those smiles on the faces of the villagers, and the skills and power and energy you leave behind. When you make one suffering person smile with hope, you feel you are winning at the same time.”

Several essays in the book concern the role of the law in addressing the climate crisis. Here, too, is a full awareness of the law’s limitations.

Litigation “takes more time than we have,” writes British lawyer and environmental activist Farhana Yamin. “I have come to the conclusion that any solutions the courts can deliver right now will not be fast enough or sweeping enough to deliver the transformational changes we need in the next few years—unless and until they are accompanied by people rising up in a global movement that is powerful enough to take on polluters and complacent politicians.”

Yamin’s essay is titled “Why Climate Lawyers Need to Break the Law.” Its opening line: “On April 16, 2019, I superglued my hands to the pavement outside the headquarters of the oil company Shell in London.” She notes that both Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela “were lawyers who first worked within the law launching campaigns based on petitions, marches, and litigation. But both ultimately chose lawbreaking as the key, decisive tool in their successful opposition to imperialism and apartheid.”

What’s needed are bodies on the line as well as arguments in the courts. Jane Fonda, who has been getting arrested in the furtherance of progressive causes since 1970, was in her eighties in 2019, when she moved to Washington, D.C., and began getting arrested on a weekly basis at “climate justice” protests. After COVID-19 struck, these were replaced by a weekly program, held virtually.

Fonda’s perspective is appropriately measured: “The law is no magic bullet when it comes to bringing about change, but if you understand its power as a tool, you can harness it to bring about the change yourself—especially if you do it with others as a movement.”

The Revolution Will Not Be Litigated even includes Redford’s list of ten “Rules for Radical Lawyers.” Among them: “Begin with a vision for genuine change,” “Listen to understand rather than to argue,” “Embrace the power of storytelling,” and “Winning the case isn’t everything. Winning meaningful change is.”

Another good piece of advice for lawyers and the people who need them: Read this book.

Felecia Phillips Ollie DD (h.c.) is the inspiring leader and founder of The Equality Network LLC (TEN). With a background in coaching, travel, and a career in news, Felecia brings a unique perspective to promoting diversity and inclusion. Holding a Bachelor’s Degree in English/Communications, she is passionate about creating a more inclusive future. From graduating from Mississippi Valley State University to leading initiatives like the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, Felecia is dedicated to making a positive impact. Join her journey on our blog as she shares insights and leads the charge for equity through The Equality Network.