Activism

/

September 5, 2025

From reactive accountability to proactive reform.

After the world watched George Floyd die under Derek Chauvin’s knee in 2020, protesters flooded the streets and hopes soared for real reform. Five years later, killings by police have actually risen—especially of Black Americans. Minneapolis’s police chief, Brian O’Hara, calls Floyd’s death an “open wound.” His challenge, shared by departments nationwide, is not only how to punish after tragedy but how to prevent the next George Floyd or Tyre Nichols.

Many in the Black community call for a different kind of justice: one that is proactive in preventing the crimes against Black people. As the Rev. William Barber and Jonathan Wilson-Hartgrove wrote, “Accountability for Mr. Floyd’s murder is not justice.” Justice demands prevention. Elie Mystal demands a concrete plan, putting it more bluntly, to “stop the cops from shooting us.”

Since George Floyd’s murder, calls have grown louder for accountability—essential but incomplete. Yes, we absolutely need to hold officers accountable and ensure that officers are punished for wrongdoing. But accountability is reactive—it comes only after a tragedy. Rarely does it drive prevention of the next tragedy. In fact, the threat of being sanctioned often creates perverse incentives—driving employees to cover up misconduct that helps explain why punishment alone fails to prevent the excessive use of force.

Fortunately, a viable option exists. By creating a reward-based culture that values community members and calms volatile situations, departments can improve public safety. This approach could be used to overcome a predictable side effect of punishment—covering up excessive force by lying, misleading, or filing incomplete or inaccurate reports.

A comparable example was faced in companies with “three strike” policies, punishing employees for having accidents. Employees at risk of being sanctioned responded by hiding their injuries—the “bloody pockets” phenomenon—fearing they’ll be fired for reporting. Once managers started to behaviorally define, measure, and reinforce safe behaviors (like “lifting with legs, not backs”), safety practices significantly improved and injuries declined. This isn’t hypothetical. A 1999 meta-analysis of 73 relevant real-world experiments found workplace accidents dropped 26 percent in the first year—and 69 percent by year five—when managers recognized workers for desired safety performance.

The Camden County Police Department in New Jersey avoids this trap by using body cameras not to punish but to reward. Chief Gabriel Rodriguez and his supervisors “review bodycam footage daily”—not only to flag violations but to identify and celebrate good policing. Officers are publicly commended for de-escalating dangerous encounters, including one where a knife-wielding suspect was subdued without harm: “They got him good. And they got him alive.”

Current Issue

Most police departments use body cameras to catch wrongdoing. Camden uses them to acknowledge de-escalation skills: building rapport (“Hey bro, what’s your name?”), taking time to ensure that no one gets hurt, calming distraught individuals: “Breathe. That’s it. You’ve got this.” “Even if you get everything justified and right,” Rodriguez said, we still bring you in to watch your videos “because we want you to do better.”

“No one should get pulled over for a traffic violation and not make it home to their family,” said Rodriguez after the fatal beating of Tyre Nichols. For a decade, Camden has upheld a department-wide goal: the sanctity of life. Camden officers know success means suspects and officers alike get home safely.

Just as reinforcing safety behaviors cut workplace accidents by 69 percent, complaints plummeted when Camden supervisors reinforced de-escalation. As reported in the ABA Journal in 2021, excessive force complaints dropped from 65 in 2014 to just three in 2020.

Camden shows what happens when body camera footage is used to recognize officers. In Minneapolis, by contrast, O’Hara lamented how infrequently “caring and compassion” is spotlighted—like officers, who shared their experience in a rare Facebook post, helping an injured man call his family and, as pictured, refilling his dogs’ water bowls.

Now imagine if O’Hara and his department could regularly share bodycam videos capturing the nuanced, warmhearted ways officers value community members. See what you think of this video (“APD Officer Uses Crisis Intervention Training to Help Man Experiencing Mental Crisis”). Watch the Atlanta officer’s approach, how he positions himself, the tone he uses—as he persuades a reluctant man to accept help and go to the hospital. Highlighting such footage could provide officers real-life models of de-escalation and inspire them to do better.

Since Camden is the only documented law enforcement case, some may dismiss it as a one-off. But the underlying principle—that what gets recognized gets repeated—is universal. Over four decades of research in more than 100 well-controlled experiments have shown that reinforcement works across settings: from reducing accidents in high-risk workplaces to improving the play execution of a youth football team. To shift focus from winning to learning, youth football coach Fred Barnett broke plays into five critical stages—from the center-quarterback exchange to the quarterback’s final action in the option play. Coaches watched from the sidelines, checking stages completed for players to see. With this behavior-based feedback, play execution rose 20 percent, while errors dropped. Even after games won, players often talked about the fine points of the stages, targeting ones still needing improvement. The lesson is clear: When positive conduct is tracked and rewarded, it grows.

Unfortunately, most department dashboards track only crime statistics, arrests, and police failures: excessive force reports, citizen complaints. No mention is made about positive police performance. If dashboards added skillful de-escalation, it would help to change the police culture.

To address that gap, I developed a behavior-based grading system for de-escalation, using publicly available videos. The rubric assesses how well officers manage encounters based on their ability to calm, listen, and resolve safely. To take into account varying interactions, grading was adjusted for compliant, protesting, attacking, and dangerous subjects. Here’s a simplified version evaluating how officers are dealing with an attacking subject:

* AAA: Repeated de-escalation, active listening, safe resolution

* AA: De-escalation, listening, safe resolution

* A: De-escalation and safe resolution

* B: De-escalation or safe resolution

* C: No de-escalation or escalation

* D: Escalation: rushing, swaggering, or risking subject injury during handcuffing

* F: Escalation: using unnecessary or excessive force on a non-attacking subject

Watch this footage (“Man Tries to Attack Officer With Needle During Arrest”), with the above rating system in hand. Decide what grade these Burlington, Vermont, officers should earn when dealing with this aggressive man, who’s wanted on a warrant, before and then after handcuffing him.

Applied department-wide, this metric would enable cities to add de-escalation success to their dashboards. Police and the public could then follow monthly progress over time.

Departments could institutionalize this addition by establishing a “merit center” to evaluate submitted footage. Officers (or partners) could submit two clips per month, showcasing officers’ noteworthy interactions. The footage would be rated using a fair, collaborative process. Officers and community members would be invited to nominate outstanding videos to be shown to the community.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

On an internal dashboard, performance would be broken down by precinct, shift, supervisor, and officer. To facilitate learning, officers would be able to download their ratings with their videos. Best of all, standout footage could be shown at roll call and CompStat meetings. Envision playing this clip (“Police officers stop fellow officer punching handcuffed woman during arrest”) and how officers might react to seeing two LAPD officers step in to intervene—moments that might have saved a life. Dashboard results would be updated twice monthly so supervisors could recognize officers in real time and use the ratings when making promotion decisions. Officers who excel at preserving life would rise in the ranks.

Skeptics ask whether such a reward-based system could have stopped Derek Chauvin. No one can know for certain. But imagine Chauvin steeped in a culture where sanctity of life was all-important. Where every officer submitted bodycam clips twice a month for merit review. Where officers routinely watched peer footage celebrating successful de-escalations. Where promotion required repeated evidence of life-preserving expertise. Chauvin might never have become a field training officer—or might have had to develop skills allowing Floyd to go home that night. Just as important, what if Chauvin’s fellow officers had been embedded in a culture that valued stepping in—and regularly watched videos of peers stopping excessive force? Perhaps one or more officers would have intervened, saving George Floyd’s life.

A reward-based culture isn’t a panacea. But it’s a meaningful, evidence-backed step toward protecting Black lives. Crucially, it’s not a rejection of accountability but a rebalancing. Civilian Complaint Review Boards and internal reviews that investigate and impose penalties for misconduct will still be essential. But why stop at documenting misconduct? Communities and departments could also track—and reward—what’s done well.

The best way to honor George Floyd and Tyre Nichols is not by punishing those who failed them. It’s by being proactive and preventing the next tragedy. A different kind of justice is within reach—one that measures what matters, rewards what works, and helps ensure that everyone gets home safely.

More from The Nation

It’s still unclear—and that’s the problem.

Dave Zirin

Paramount is reportedly set to pay between $100 million and $200 million for “The Free Press” and will install Bari Weiss at the top of CBS News.

Jack Mirkinson

The administration’s decision to deploy military lawyers as immigration judges is terrible and illegal, but when has that ever stopped Trump?

Elie Mystal

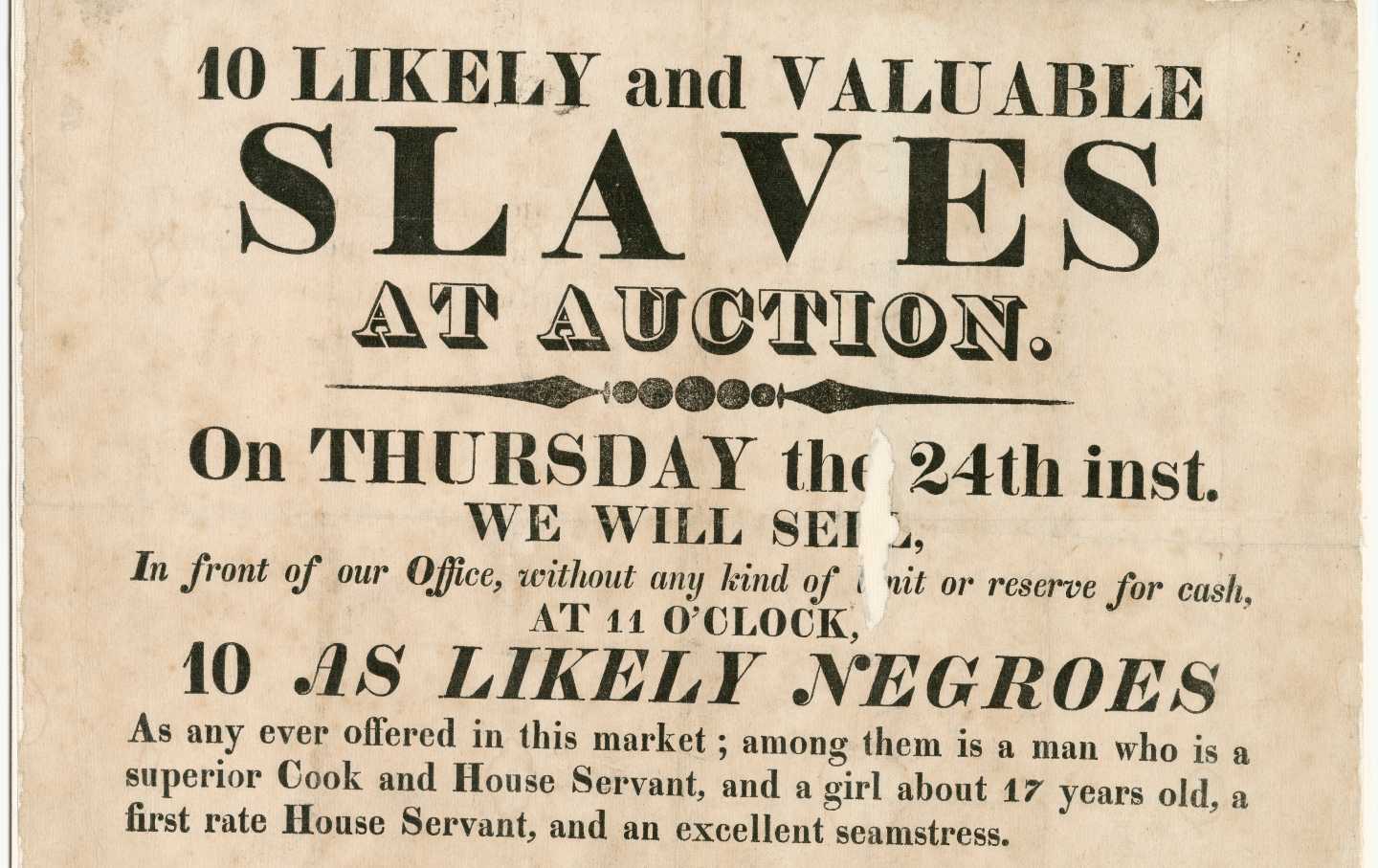

Calls to attenuate the brutality of slavery in museum depictions is absurd when our institutions already downplay one of its most horrific features.

Channing Gerard Joseph

Felecia Phillips Ollie DD (h.c.) is the inspiring leader and founder of The Equality Network LLC (TEN). With a background in coaching, travel, and a career in news, Felecia brings a unique perspective to promoting diversity and inclusion. Holding a Bachelor’s Degree in English/Communications, she is passionate about creating a more inclusive future. From graduating from Mississippi Valley State University to leading initiatives like the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, Felecia is dedicated to making a positive impact. Join her journey on our blog as she shares insights and leads the charge for equity through The Equality Network.