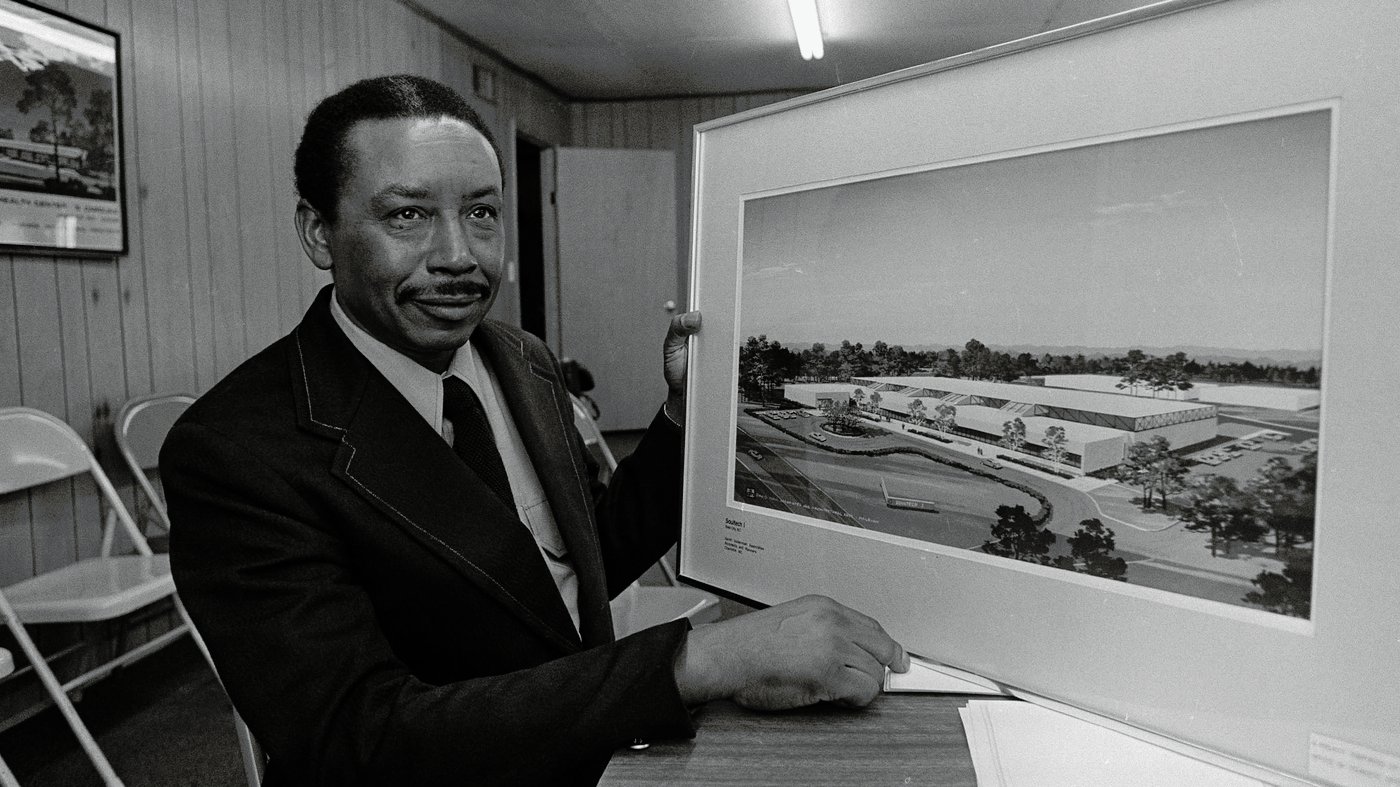

Former civil rights lawyer-activist Floyd McKissick, poses with an architect’s rendering of Soultech I, the first permanent building that will be part of the future “Soul City,” to be built in Warren County, N.C., June 20, 1974.

Harold Valentine/AP

In the late 1960s, a man named Floyd McKissick began building his dream: a brand-new community in rural North Carolina, on a plot of land a third of the size of Manhattan — complete with factories, an airport, a bustling city center and tens of thousands of residents living in Brady Bunch-esque houses. The twist? It would be be built by Black business and enterprise: a capital for Black capitalism, as the New Yorker called it.

This week on the show, we dive deep into Soul City: one of the most audacious (and controversial) experiments in Black capitalism. For a little while, it had the backing of some of the most powerful people in the United States, and it almost happened.

At the time, the experiment was widely covered and debated in the news. And yet, today, very few people have heard of it.

To learn more about this would-be utopia, we hit up Thomas Healy, the author of a new book called Soul City: Race, Equality, and the Lost Dream of an American Utopia.Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Can you tell us about Floyd McKissick?

He was a major civil rights leader during the 1960s. His career actually began in the 1950s. He was born in the mountains of Asheville, North Carolina, in 1922. He served in World War II, was awarded a Purple Heart and graduated from Morehouse a few years after the war. He went to law school, and then, he set up shop as a lawyer in Durham.

He was primarily interested in civil rights, and he gradually became one of the most important civil rights leaders in North Carolina. For a period of time in the 1960s, he was the head of the Congress of Racial Equality, which at the time was one of the big five civil rights groups. And he spoke at the March on Washington, and along with Martin Luther King and Stokely Carmichael, he led the March Against Fear in 1966. And he was one of the most prominent voices advocating economic equality for Black people during the 1960s.

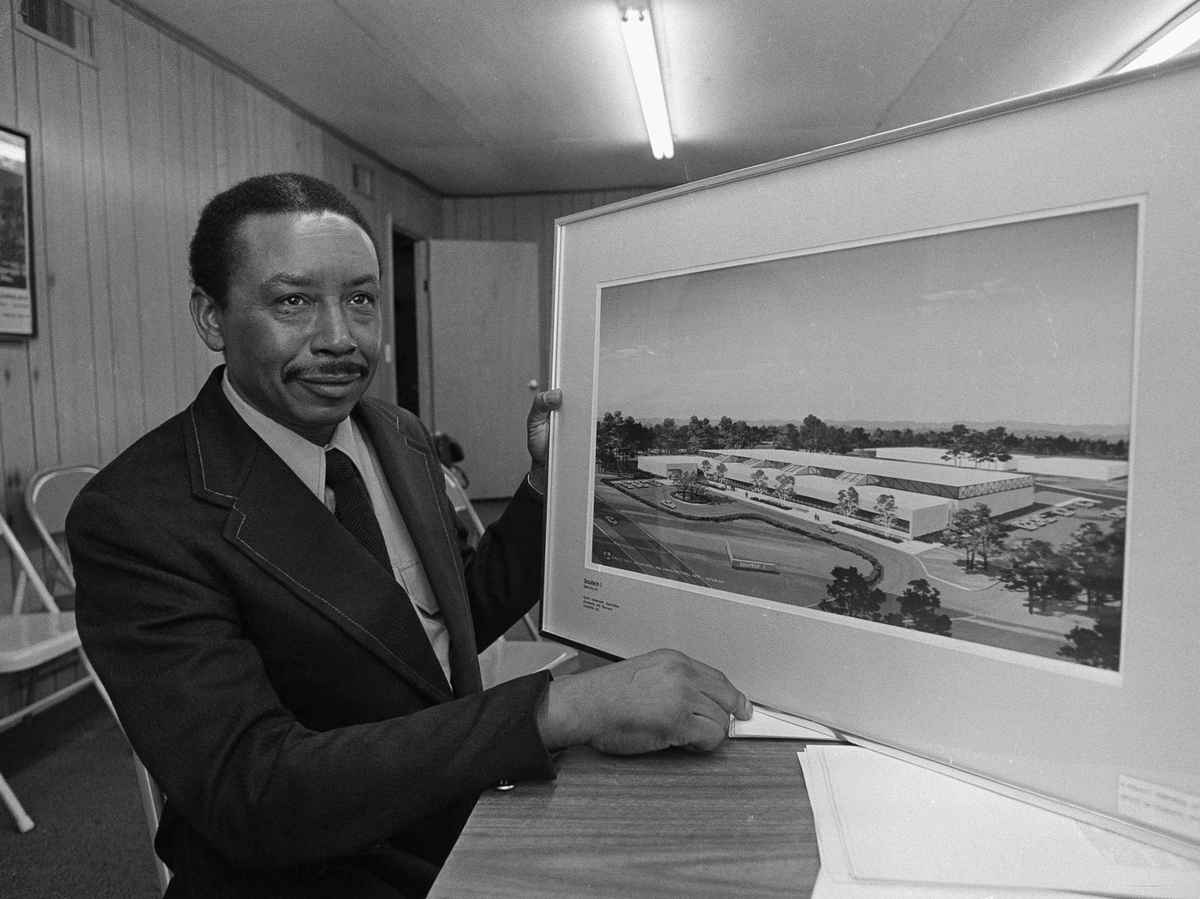

Thousands of marchers assemble for the last leg of the Mississippi March in 1966. In the front row, from left are: Mrs. Juanita Abernathy, the Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Mrs. Coretta Scott King, Dr. Martin Luther King, James Meredith, Stokely Carmichael of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee and Floyd B. McKissick, national director of the Congress of Racial Equality.

Charles Kelly/ASSOCIATED PRESS

For those who aren’t familiar with CORE, what did the group — and McKissick — want to acomplish?

In the mid ’60s, CORE became known as one of the more militant civil rights organizations. It shifted the focus from integration to the problems in Black neighborhoods and the issues of poverty, the lack of adequate housing and lack of economic opportunity. And, you know, McKissick was really sort of leading that; he was one of the figures who really spoke strongly about, you know, the importance of economic equality to the Black freedom struggle.

And when Black power became the rallying cry in the summer of 1966, CORE became one of the leading proponents of Black power. They basically thought that there were six elements to Black power, economic self-sufficiency, political representation, improved self-image, the development of Black leadership, the enforcement of federal laws and the mobilization of Black consumers. But McKissick thought that the most important aspect of Black power was economic power. He said, if you don’t have any bread in your pocket, you know, what good is it to you to be able to sit at a hamburger counter?

So that was really the goal: to find a way for Black people to share in the wealth of America, and to share in the wealth that’s generated in the capitalist system. And McKissick believed that it makes sense to work within that system because, I think he thought you had a better chance of working within that system than trying to overturn that system.

How did McKissick come to believe that there should be a Black-run city in the U.S.?

He did say many times that the idea came to him after World War II, when he and his Army unit were helping to rebuild French villages that had been destroyed by shelling. He described watching French planners and engineers put their cities back together again. And he had this idea that, if people in Europe could rebuild their cities, why couldn’t Black people in America build new cities from scratch?

That might have been the moment when it sort of crystallized for him. But it seemed to me that a lot of the motivation and the inspiration for Soul City came out of experiences that he had when he was growing up in Asheville, North Carolina, and saw racial injustice around him and experienced it himself. He described himself feeling like a Black boy in a white land. And I think that he wanted to create a place where he wouldn’t feel like a stranger, where he would feel at home and welcome. Now, that doesn’t mean that he wanted it to be separatist. You know, it doesn’t mean that he didn’t want to be around people of other races. But I think that he wanted to feel like he belonged. Everybody wants to feel like they belong. And I think that a large part of the impetus behind Soul City was the desire not to feel like you’re a second class citizen, not to feel like you’re Black first and American second.

You wrote in your book that McKissick never envisioned Soul City to be just for Black folks; he wanted it to be a multiracial town. But he also just didn’t envision it as a town for just any Black folks. What were the specifications that he wanted in the residents of Soul City?

The requirements were more for the people who worked at Soul City than for the people who lived in Soul City. This was a serious undertaking, and he needed serious people to be involved in it. When he was recruiting a staff, he was looking for people with the qualifications they needed: engineers, planners, people with a background in building social systems and health care, and accountants. He needed people with very specific skills, because he had big ambitions.

But as far as who would live in Soul City, he didn’t want this to be a community only for well-educated people or people of a certain income level. Most of the people that he envisioned living and working in Soul City would be involved in industry. They would be factory workers, business people, from all walks of life. But he definitely did not want to restrict this to “the talented tenth” or anything like that. His whole emphasis at CORE had really been on improving the lives of poor people in Black neighborhoods.

In McKissick’s most ambitious imaginings, what did he envision this city to be? What did it look like? What would be there? Who would be there?

So it would have been about 50,000 people by the year 2000. But obviously, 20 years later, it probably would have been bigger than that now. Physically, it would have been a relatively compact city; he was planning it on about 5,000 acres. It would have been more dense than your kind of typical, sprawling, you know, modern American city. Because it was to be built from scratch, all of the infrastructure would have been new. He was trying to take advantage of new ideas in terms of planning a city; all of the electrical lines were going to be buried underground. The road system was designed to sort of funnel traffic efficiently. There were going to be a lot of bike paths and walking paths to the woods. So there would have been a combination of urban and pastoral, with a lot of green space.

And then, there would be neighborhoods that were pretty compact, little community centers in the middle of each, and one major town center. They never got very far in terms of the architecture, but when you look at the sketches, it looks to me like the architecture of The Brady Bunch.

One of the strangest elements of the story is that Richard Nixon ended up becoming a big proponent of Soul City. How did that partnership come to be?

Nixon was a strange figure, a complicated figure. Jet magazine referred to him as the civil rights workhorse of the Republican Party when he was vice president. After Nixon helped ensure passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1957, Martin Luther King Jr. praised Nixon for his help and his courage in getting the law passed. The NAACP named him an honorary member in the late 1950s. When he was running against Kennedy, for a large part of that campaign, Nixon was viewed as more progressive on issues of race than Kennedy. It was only at the end, you know, when the Kennedys helped get King out of jail, that things flipped.

So Nixon had a complicated past. And, you know, I think he was trying to have it both ways. He wanted to use the “Southern strategy” that he had seen work. And he also wasn’t willing to give up entirely on the Black vote. He had this whole appeal to what he called the silent majority. And I think he thought that there was a Black silent majority that he could appeal to and that Black capitalism was the way to attract Black votes without alienating whites. And so he gave a speech in May of 1968 in which he praised Black capitalism, and said that it was much more in alignment with Republican principles than Democratic principles and made a play to attract Black votes.

He called it the real Black power, right?

Right. And in that sense, he and McKissick agreed that capitalism, or having control over capital, was power. And Nixon sort of reached out to the proponents of Black capitalism. Now, McKissic didn’t support him in 1968; McKissick was a pretty harsh critic of Nixon’s in the early years of Nixon’s presidency. He called him the leading proponent of law and order racism. But when he needed money for Soul City, he realized that he was going to have to appeal to the Nixon administration.

Before the 1972 election, McKissick reached out to some friends he had in the Nixon administration, and proposed that they join together in an effort to get out the Black vote for Nixon. And Nixon welcomed that support. The night before Nixon was inaugurated for his second term, he invited Floyd McKissick and his wife, Evelyn, to join him at a concert at the Kennedy Center. And so they shared a box with the president, because that’s how grateful Nixon was for McKissick’s efforts on his behalf. So there was an element of pragmatism and expediency in McKissick’s alliance with Nixon, no doubt about that. You know, he was very clear eyed about it. But I think he thought that’s how politics worked, and that he wasn’t doing anything any different than what white businessmen. And so it was this strange alliance that each person thought had benefits for them.

So how much did the Nixon administration end up pledging to Soul City?

Basically, they were going to guarantee bonds that were going to be issued on Soul City’s behalf, and the total amount that they said they would guarantee was $14 million. McKissick never actually got $14 million. He ended up getting $10 million. And then the Nixon administration also awarded him a variety of grants to help build some of the infrastructure for Soul City. And then, he continued to get some of those grants even after Nixon resigned — from the Ford administration and then from the Carter administration. So it’s hard to put an exact price tag on how much money he got solely from the Nixon administration. He ended up getting pretty substantial financial support, but not nearly enough to to accomplish what he was trying to accomplish. And so McKissick was sort of left without a lot to show for his alliance.

But that federal support changed the popular perception of Soul City, though, right? He was suddenly sort of getting much more positive attention in the mainstream press.

Yeah, absolutely. I think a lot of people were pretty amazed that McKissick managed to get that loan guarantee. And it changed a lot of people’s minds about the feasibility of Soul City, and the people whose minds it changed the most or the people in the county where he wanted to build it: Warren County. The county was controlled by whites, even though it was two-thirds Black. But when those county officials saw the kind of money that McKissick was getting from the federal government, they jumped right on board.

I think that’s an important part of the story — the way McKissick was able to bring on board all of these local whites who had initially been skeptical and even hostile to Soul City. At one point he said, sometimes if you want to help yourself, you have to help others, too, which is a pretty pragmatic way of looking at it. But I think that what he was trying to tell these people in Warren County was that, look, I’m not going to just be helping Black people. I’m going to be helping everybody here. And this was a really poor part of the state. And when those officials saw the kind of money that was coming in, they were happy to have Soul City at that point. Self-interest is a huge motivator. And I think he leveraged the self-interest of local officials to get them to support Soul City.

To learn more about what happened next, listen to the rest of our conversation of this week’s episode wherever you get your podcasts, including NPR One, Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Pocket Casts, Stitcher, Google Podcasts and RSS.

Felecia Phillips Ollie DD (h.c.) is the inspiring leader and founder of The Equality Network LLC (TEN). With a background in coaching, travel, and a career in news, Felecia brings a unique perspective to promoting diversity and inclusion. Holding a Bachelor’s Degree in English/Communications, she is passionate about creating a more inclusive future. From graduating from Mississippi Valley State University to leading initiatives like the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, Felecia is dedicated to making a positive impact. Join her journey on our blog as she shares insights and leads the charge for equity through The Equality Network.