The role of a lady-in-waiting, as detailed in Glenconner’s first book, lies somewhere between that of a friend or a confidante and that of a personal assistant—identifying the location of the bathroom on a royal visit, or insuring that a royal visitor is served the right thing to drink. (In Princess Margaret’s case, a gin-and-tonic at lunch and whiskey with water in the evening.) Ladies-in-waiting are not recompensed, other than by proximity to royalty. Glenconner received only a modest dress allowance for her attentions to Princess Margaret. Even after decades of close friendship, Glenconner addressed the Princess as “Ma’am,” while being addressed herself as Anne. “I would have been very uncomfortable calling her anything else,” she writes.

“Lady in Waiting” paints a fond, if not always flattering, portrait of Princess Margaret, whom Glenconner had known from early childhood. Holkham Hall is a short drive from Sandringham, one of the Royal Family’s country residences. Glenconner writes that the Princess was “naughty, fun and imaginative—the very best sort of friend to have.” They used to dig holes in the sand on Holkham Beach, in the hope that people would fall into them. Princess Margaret, Glenconner believes, was never allowed to shed her role as the wayward royal sister. “The fact she enjoyed the company of creative people, a cigarette and a drink made it easy to cast her as a rebel,” she writes.

Princess Margaret was able to indulge in those tastes in sybaritic Mustique, where in the late sixties Colin Tennant gave her a piece of land as a gift. When Tennant took her to the site, she surreptitiously pulled up the wooden stakes demarcating it, extending the perimeter. She then told Tennant, firmly, “I think I ought to have a bit more land.” Mustique became for Princess Margaret a much valued escape from the pressures of palace life, while she became for Tennant the most valuable of marketing assets.

At other times, Glenconner provided Princess Margaret with a taste of more mundane activities: on visits to Glenconner’s Norfolk home, the Princess sometimes dismantled the chandelier and cleaned it in the bathtub. Another bond between them was their shared experience of marital unhappiness. In 1960, Princess Margaret married Antony Armstrong-Jones, a society photographer who was ennobled as the Earl of Snowdon after their wedding. “Like Colin, Tony was unpredictable,” Glenconner writes. “He was eccentric and extremely demanding, often rubbing people up the wrong way. But, just like Colin, he could be incredibly charming.” Snowdon had his own tactics for belittling his wife: “Lady in Waiting” tells how he used to leave insulting notes in Princess Margaret’s chest of drawers. (One read, “You look like a Jewish manicurist and I hate you.”) Princess Margaret rarely unburdened herself about Snowdon’s behavior, and encouraged her lady-in-waiting to exercise similar restraint. Glenconner writes, “Once when I didn’t open a door quickly enough for Colin, and he blew up and she saw me start to cry, she just said, ‘Stop that at once, Anne. It’s absolutely no use.’ . . . I learned a lot about stiffening one’s spine and getting on with it from Princess Margaret.” Glenconner is impatient with what she sees as the excessive sensitivity of younger generations, including royals. Twice at recent public events, when she was asked for her opinion of the Duke and Duchess of Sussex’s decision to move to California, she shot back, “The farther away the better, as far as I am concerned.”

In 1973, at a gathering at Glen House, Princess Margaret, then forty-two, met a garden designer seventeen years her junior, named Roddy Llewellyn. They went on to have an eight-year-long relationship, which contributed to her divorce, in 1978. At the time, it was a major scandal; as Glenconner writes, Princess Margaret was “the first high-profile member of the Royal Family since King Henry VIII” to end a marriage. The houseparty is dramatized in “The Crown,” with Helena Bonham Carter, as the Princess, lounging by the side of a pool with Nancy Carroll, as Lady Anne, pointing out possible beaux. Glenconner says that, in fact, she merely invited Llewellyn to make up the numbers at the party. In “Whatever Next?,” she writes of the show, “They made it look as if I was pimping for her,” remarking, “That would be taking being a good hostess a bit too far in my opinion.” Although she enjoyed the initial episodes of “The Crown,” with their representation of the coronation and the young Queen’s adjustment to the demands of her role, she found the distortions of later seasons—such as the suggestion that the Duke of Edinburgh bore some responsibility for his sister’s death in a plane crash—unnecessary and hurtful. “It’s fantasy,” Lady Glenconner tells the capacity crowds who show up to see her at literary festivals, and before whom she clearly revels in finally being the center of attention. “I’m the real thing.”

When “Lady in Waiting” was first published, Glenconner did not dare send a copy to the Queen, who, even as a child, had disapproved of the way Anne and Princess Margaret rode tricycles around the grand rooms of Holkham Hall, or jumped out from hiding places to surprise footmen carrying silver trays from the kitchen. After the memoir was out, however, Glenconner bumped into Sarah Ferguson, Duchess of York, who assured her that “the boss”—as Fergie characterized the monarch—had loved the book. Glenconner then sent the Queen a signed copy.

It saddens Glenconner to drive past Windsor Castle these days, now that the Queen is gone, but she is good friends with King Charles, whom she has known since he was a boy. He was “like a younger brother to me,” she writes. One of her early memories of Charles is as a four-year-old: on the day of Elizabeth II’s coronation, Glenconner saw him pick up his mother’s crown. “He has got all these very, very good ideas,” she told me, speaking of Charles’s long-standing commitment to environmentalism and to the regeneration of local economies. “He’s got great passion.”

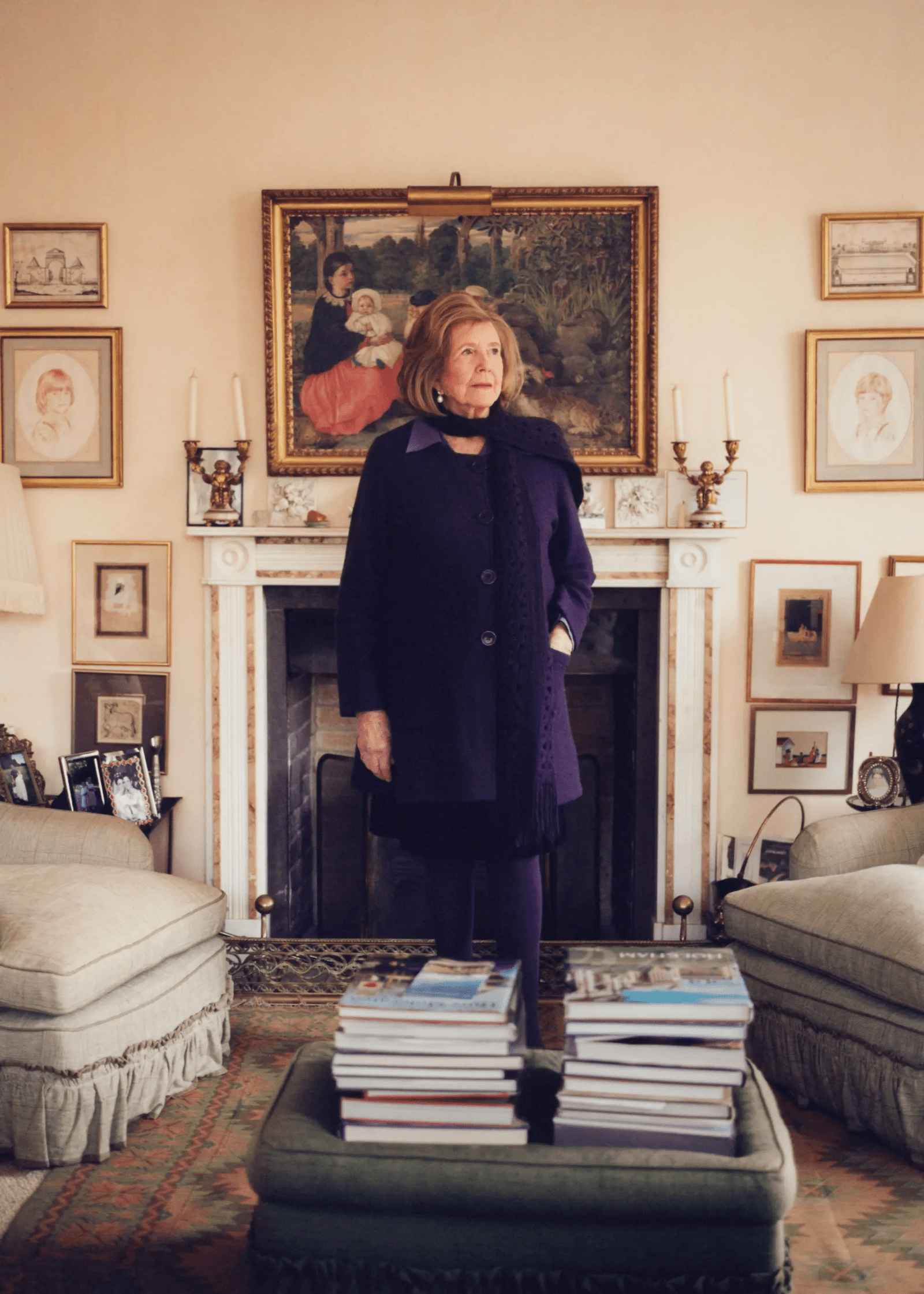

When the King is at Sandringham, he sometimes invites Glenconner over for dinner, sending a car to pick her up. She’d been at Sandringham not long before we met at Holkham Hall, and there had been talk of Lady Susan Hussey’s resignation. Lady Susan’s daughter, Lady Katherine Brooke, was recently appointed by Camilla as one of six Queen’s companions, a newly created designation for a modernizing monarchy: there will be no more ladies-in-waiting.

There had also been discussion of King Charles’s coronation, which will take place in May, on a scale much reduced from that of Queen Elizabeth. There will reportedly be only two thousand guests, as opposed to the eight thousand who were at Westminster Abbey seventy years ago. Competition for seats at the Abbey is inevitable, with not every titled grandee guaranteed a spot. Glenconner said, “I think the dukes will all come, because they are part of the ceremony—they give their liege, or whatever it is. But I think the other peers and peeresses will have to ballot.”

As the mere eldest daughter of an earl, Glenconner is unlikely to make the cut if rank is the sole factor. But as a family friend—and especially as a rare living link to the coronation of 1953—she hopes to be invited. She is not taking any chances at being overlooked. “They have to be reminded,” she told me. “Which I did.” Finding herself next to King Charles, she had made full use of the opportunity. “I am going to be a bit cheeky now,” she informed His Majesty, putting in her request right then. Why ever not? There was nothing to be gained by waiting.

Felecia Phillips Ollie DD (h.c.) is the inspiring leader and founder of The Equality Network LLC (TEN). With a background in coaching, travel, and a career in news, Felecia brings a unique perspective to promoting diversity and inclusion. Holding a Bachelor’s Degree in English/Communications, she is passionate about creating a more inclusive future. From graduating from Mississippi Valley State University to leading initiatives like the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, Felecia is dedicated to making a positive impact. Join her journey on our blog as she shares insights and leads the charge for equity through The Equality Network.