Activism

/

November 6, 2025

It’s time for us to reconnect with the radical, system-changing spirit that was once at the heart of our field.

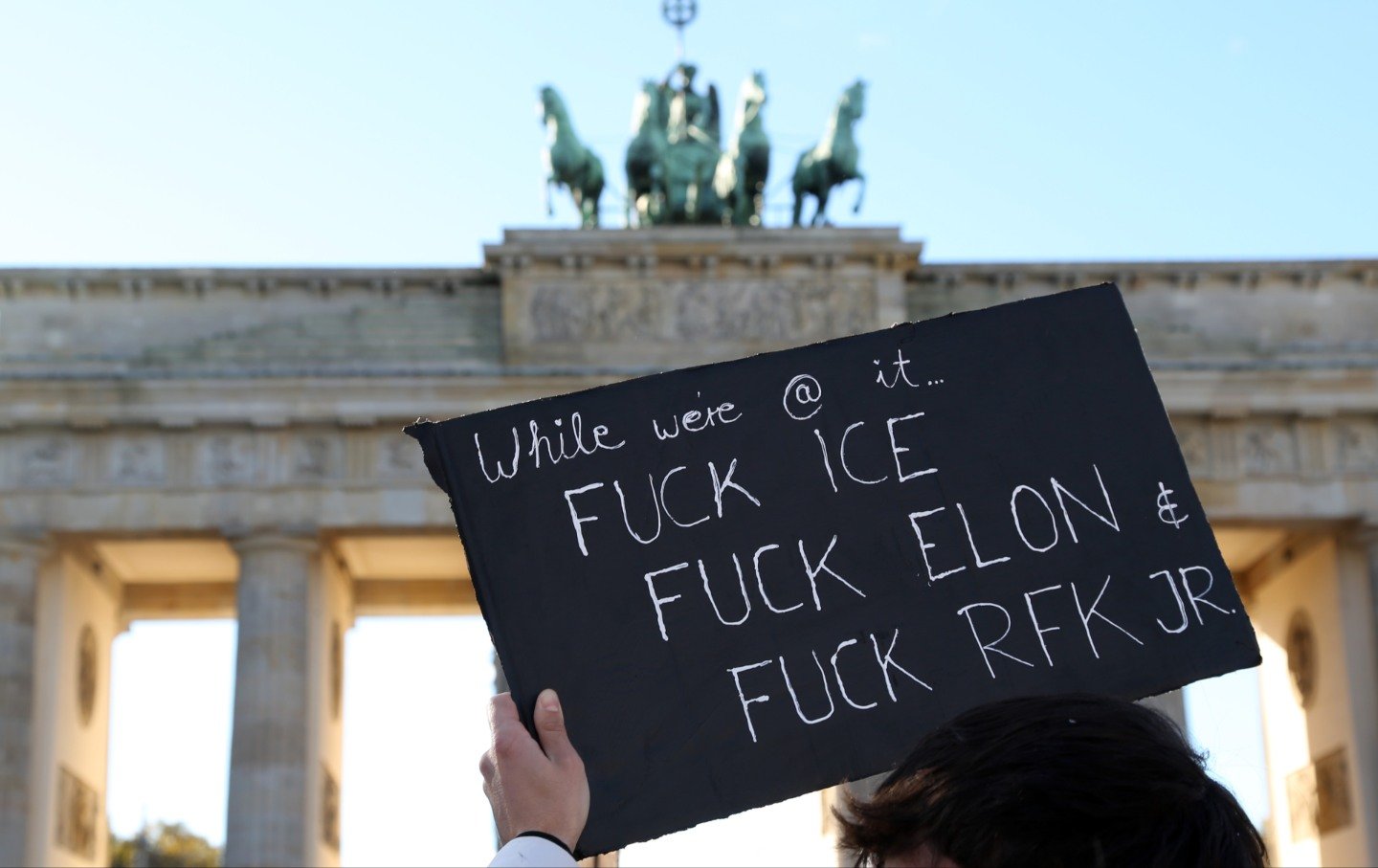

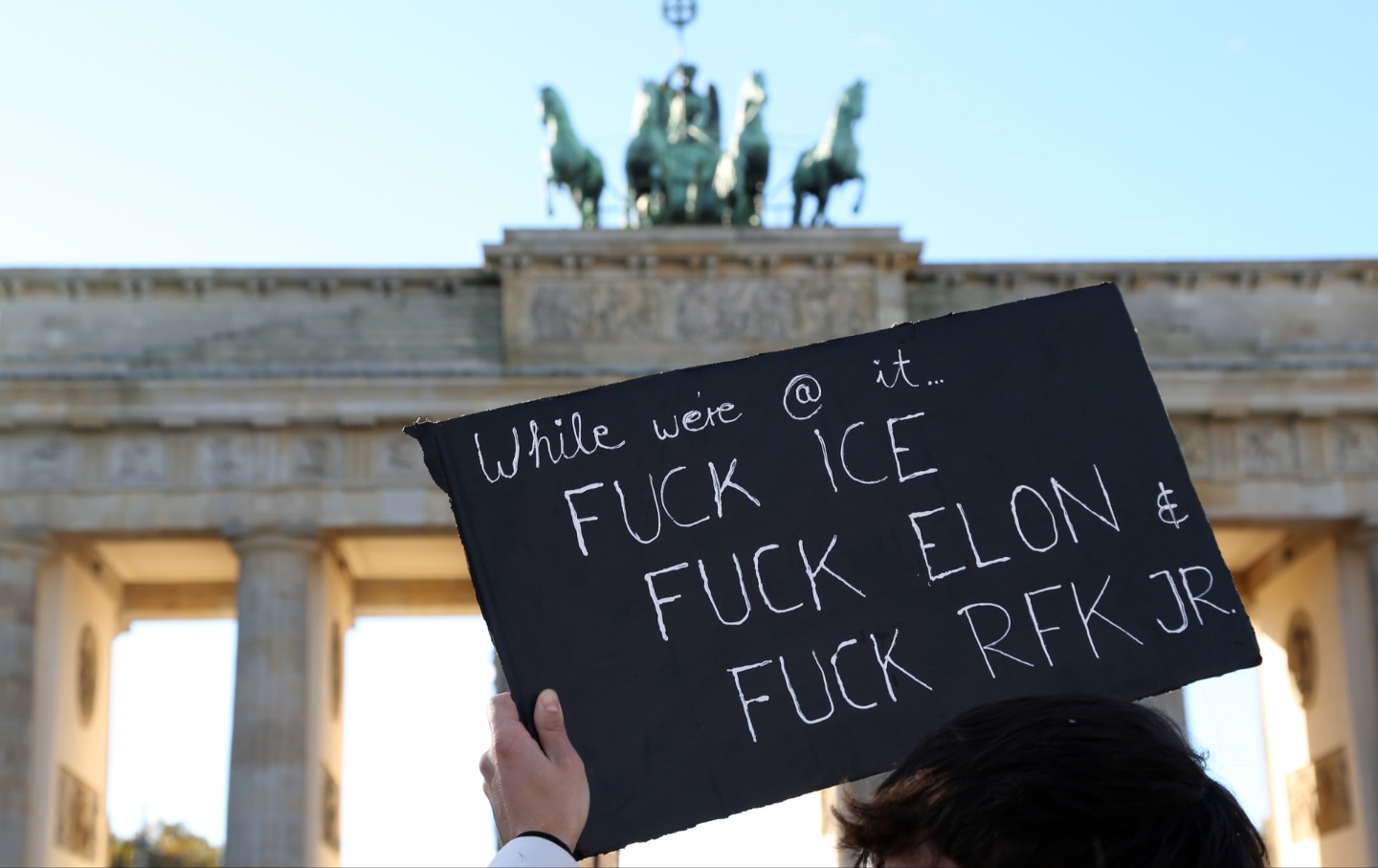

A sign at a protest outside the US embassy in Berlin on October 18, 2025.

(Adam Berry / Getty Images)

This is an edited version of a speech I gave at a recent meeting of the American Public Health Association in Washington, DC.

Ed Yong was the chronicler of our most recent plague years. His reporting on Covid-19 for The Atlantic won him a Pulitzer, but constant reporting on those who suffered the most during the pandemic took its toll on him. He walked away from The Atlantic, and from reporting on the disease, in 2023, with his final pieces largely focusing on long-Covid sufferers fighting for their survival. You should listen to a lovely and heartbreaking talk he gave for the XOXO Festival last year, in which he explained why he walked away when he did. It’s. It’s clear he needed to go, but Ed was central to framing the pandemic in its larger social and political context for a general audience and I miss his voice.

I want to talk about one of his stories—an earlier one—that was before its time and is still very much of the moment even now. It was in October 2021, and it was called “How Public Health Took Part in Its Own Downfall.” In the piece, he makes a case that Amy Fairchild and colleagues made before him in their own article “The EXODUS of Public Health: What History Can Tell Us About the Future” in 2010 in the American Journal of Public Health. Here’s the case: We were warriors once. That is, for decades, those of us working in public health were campaigners who fought for better sanitation and clean water, better working conditions in the factories of the new Industrial Age, better housing, and so much else that gave us the longer and healthier lives we take for granted today.

And then we gave up the fight. Ed and Amy contend that the rise of American medicine was the death of public health in some ways. Amy’s piece quotes Hibbert Hill and his book The New Public Health: “The old public health was concerned with the environment; the new is concerned with the individual. The old sought the sources of infectious disease in the surroundings of man; the new finds them in man himself. The old public health…failed because it sought them …in every place and in every thing where they were not.”

In the shadow of medicine’s ascendancy, we cast aside the explicit and direct political nature of our work and became medicine’s poor stepchild. We became scientists and clinicians first, and made our solutions technocratic, based on interventions packaged like pills for populations. Yes, this is overstated in some ways—but in other, fundamental ones, it really isn’t. My own public health school only recently emerged from the shadow of the school of medicine and from under the thumb of its deans, who had little knowledge and even less interest in what we did. And many in our profession repeated the mantra of “public health should not be political” over the past five years, including several deans of schools of public health who bemoaned the activist work that many of us have done and continue to do.

Clearly, we need to see ourselves once again as campaigners above all, and join forces with the social movements of the day. But that is just a first step. In 2020, another Amy, my colleague Amy Kapczynski at Yale Law School, and I wrote a series of pieces for the Boston Review. In these pieces, we laid the blame for our excruciating vulnerability to this new pathogen not solely on the sorry state of public health and healthcare infrastructure in the US (though obviously they both played a part), but something more fundamental—the economic basis of American life. This rapacious, extractive, and exploitative system was already making us sick long before SARS-CoV-2 emerged, keeping us from caring for ourselves and for each other in the broadest sense and using institutions, from the prison to the hospital, to manage the downstream effects of what the system had wrought.

Current Issue

Five years later, we’ve seen this system metastasize into its most fulminant form, into pure extraction, exploitation, plunder, ramping up the carceral state into a hypertrophied internal security apparatus to manage all of us. If SARS-CoV-2 was the plague of the first part of this decade, the Trump administration, this Congress, the Supreme Court, and all the hangers-ons, enablers, fellow travelers, and cowards in civic institutions, from the media to big business to our own universities, are the plague of its second half.

So where do we go now? Yes, as I said, we need to be campaigners again, to center our work in the fight for political change. That alone will chafe for some. Those of us who depend on grants or work for state institutions are clearly not paid to be political, and the demands of our jobs make that political work extracurricular. But the problem goes deeper than that. I don’t think we can focus on public health alone any longer (if we ever could). I’ve worked on HIV/AIDS for over 35 years. We made some great strides, amazing ones—I am living proof of what we achieved as I’d be dead long ago without the drugs I take every morning—but all the programs we fought for were concessionary victories. Yes, they were real and had tangible effects on millions of lives. But we now know that one man can make all of this go away. The destruction of PEPFAR, the CDC, NIH, SAMSHA, NIOHS, the FDA—all of it can go up in smoke in an instant.

This means we have to strike at the heart of the beast. And this is where I’ll lose more of you still, and in more than one way. If what ails us is the fundamental nature of racial capitalism and patriarchy, some of you will check out. These things are base and superstructure—they are not going away anytime soon. And yet, we cannot ignore them if we want a better future. I am not asking you to “smash capitalism” or try to “escape” from it into your own private Idaho. The late sociologist Erik Olin Wright suggested that the idea of smashing and escaping capitalism is not realistic, practical, or even useful. But he offered us alternatives:

If you are concerned about the lives of others, in one way or another you have to deal with capitalist structures and institutions. Taming and eroding capitalism are the only viable options. You need to participate both in political movements for taming capitalism through public policies and in socioeconomic projects of eroding capitalism through the expansion of emancipatory forms of economic activity.

This is something we can all do—in fact, I would suggest that many of us already are working in these registers. But where and how do we do it, more of it? I think it leads us to organizing.

The late Jane McAlevey contrasted advocacy, mobilization, and organizing. Advocacy, she said, was a tool most often wielded by elites using the courts or other policy apparatuses to make change. Mobilization consisted of getting your own people out to campaign for an issue. But organizing was different. It was about expanding the pool of people who will fight for what you want. Organizing for McAlvey was mass, inclusive, and collective—the source of actual power versus pretend power. And labor has won victories in the past and into the present when they organize to win in this way.

Finally, this leads us to the work of Erica Chenoweth from Harvard, who suggests that mass mobilization doesn’t mean mobilizing everyone—that 3.5 percent of a population coming out to resist can topple a dictator. But that’s still millions of people. One-off protests are great, but we need to concentrate on organizing to achieve political power now, locally, first, and moving upwards. This is why our new group, Defend Public Health, is focusing on building state-based chapters—the idea is to figure out how to build a mass movement for public health writ broadly, to secure lasting change from the ground up. There are other ways to do this for sure, but doing it is key. There is no time to lose. Figure out who is doing real organizing near you, link up now, and get to work to bring public health to the table. Last weekend, Zohran Mamdani’s campaign set a goal to knock on 200,000 doors in New York City in one day. This week, he won his election. That should be the scale of our ambition—to reach out and connect at scale, to start the conversations in our communities, build a movement, and then win. We can’t go back to the way things were, nor should we hope for a simple restoration of the status quo from 2024 or 2019. We are all tired, anxious, depressed—I know I am—but there is no way out of this moment, except through it.

More from The Nation

Nearly a decade after promising to withdraw millions in fossil fuel investments, the University of Massachusetts has stalled on its clean energy transition. What happened?

StudentNation

/

Eric Ross

Kristi Noem visited the Twin Cities and decried out-of-control crime. Is a federal occupation next?

Alyssa Oursler

Meet Angelica Vargas, one of the most prominent of a new kind of activist: the ICE chaser.

Malavika Kannan

The city’s anti-ICE actions and No Kings demonstration have commanded mass attention, but still are no match for the impunity of the MAGA deportation state.

Nathaniel Friedman

Veteran activist Cleve Jones on the importance of immediately and effectively carrying forward the promise of No Kings rallies and marches.

Cleve Jones

We asked six student writers—in Indiana, Alaska, Alabama, and more—to report on the demonstrations in their area.

StudentNation

/

StudentNation

Felecia Phillips Ollie DD (h.c.) is the inspiring leader and founder of The Equality Network LLC (TEN). With a background in coaching, travel, and a career in news, Felecia brings a unique perspective to promoting diversity and inclusion. Holding a Bachelor’s Degree in English/Communications, she is passionate about creating a more inclusive future. From graduating from Mississippi Valley State University to leading initiatives like the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, Felecia is dedicated to making a positive impact. Join her journey on our blog as she shares insights and leads the charge for equity through The Equality Network.