July 7, 2025

As food in Gaza becomes increasingly scarce, activists are pushing their bodies to the limit in solidarity.

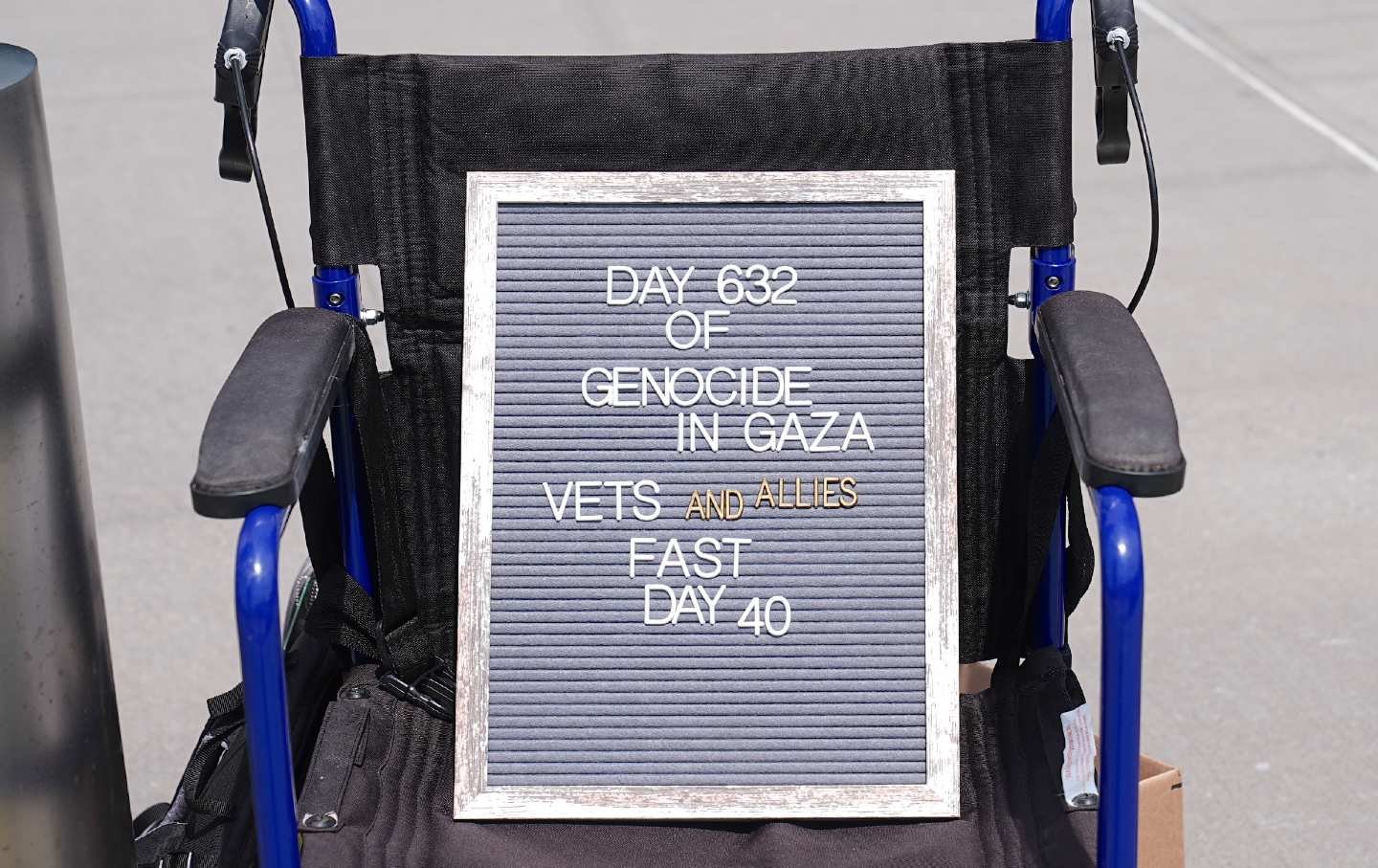

A sign tracking the numbers of days that Veterans for Peace and allies have fasted for Gaza sits in front of the United Nations Mission building in New York City on June 30, 2025.

(Selcuk Acar / Anadolu via Getty Images)

On June 30, Mike Ferner spattered a gallon of cow’s blood over the US Mission to the UN as portraits of Donald Trump and J.D. Vance looked on from behind the glass façade. “Here, United States, have some blood!” he said as it dripped down the windows. “You like shedding it all over the world so much? There you go!”

Ferner, the former national director of Veterans for Peace, then led members and supporters in a march around the block to the Israeli consulate, where the protesters lay down in the street, blocking traffic.

The blood spattering, march, and die-in marked the end of a 40-day fast organized by Veterans for Peace to demand that Israel allow the UN to distribute full humanitarian aid to Gaza and that the US stop sending Israel weapons. Over 800 participants conducted various types of fasts in solidarity, but the core group of Veterans for Peace activists restricted themselves to 250 calories per day—at one point the average daily caloric intake in parts of the Gaza Strip, which doctors consider to be a starvation diet.

Over almost two years of genocide, Gaza has descended into famine and near-famine conditions on a semiregular cycle: people starve to death; after sufficient international outcry, Israel allows food to trickle in; the situation abates a little, until aid is cut off again. This spring, the longest total blockade yet—over 11 weeks—once more prompted warnings about the risk of famine. Over the past month, the IDF has lured starving people to outposts of the US-backed Gaza Humanitarian Foundation, only to gun them down. Hundreds have died.

The Veterans for Peace activists are careful to distinguish their fast from an indefinite hunger strike. But there are still risks. Ten days in, one 72-year-old activist was told to stop fasting or risk organ failure. Three weeks in, 74-year-old Ferman was admitted to the hospital; he was told that his potassium levels were not compatible with life. “Obviously, people in Gaza don’t have that option,” Ferman said. “They just die.”

Twenty-three-year-old Joy Metzler participated in the fast as a member of Veterans for Peace. She had initially joined the military because, growing up in the wake of 9/11, she believed what she’d always been told: that the United States represented justice and peace abroad, and that it could only maintain that peace through military strength. After graduating from the Air Force Academy as a second lieutenant in June 2023, she enrolled in a graduate program for aerospace engineering that fall. A month later, the bombs started falling on Gaza.

Current Issue

Disturbed by the destruction of university encampments, Metzler began talking with members of Veterans for Peace. She began to question not only what the US was enabling in Palestine, but also its destabilizing military interventions around the world. By August 2024, she had applied for conscientious objector status. And on the last day in June, she joined the die-in at the UN, lying down in the street with the other protestors.

The writer Eileen Myles, who participated in the die-in, remembered that moment vividly. “The sky was so blue and so open,” they said. “And there was a bird flying over, and it felt like a vision of freedom, momentarily.” They and nearly 30 others were arrested soon after.

Veterans for Peace aren’t the only activists choosing to publicly protest the US’s role in the war by fasting. People around the world are doing so: doctors in France, activists in Brussels, mothers in Scotland. In Chicago, on June 16, 12 members of Jewish Voice for Peace launched an indefinite hunger strike, demanding an end to the blockade, the genocide, and US military aid to Israel. On July 4, after 18 days of no food at all, the four remaining members came to the decision to end the strike.

“Over the last 20 months, I’ve protested, I’ve been arrested, I’ve called my representatives,” said activist Ash Bohrer. They’d been taking significant risks long before October 7, including using their body to shield Palestinian activists from armed IDF soldiers. Still, the strike was intense. “We’ve signed some very scary medical and legal documents,” Bohrer said, speaking with The Nation 12 days in. “People are already starting to feel the medical effects of starvation on our bodies.”

At the time, that included intense headaches, nausea, weakness, body aches, brain fog, and the inability to regulate their body temperature. All of the strikers, Bohrer said, relied on wheelchairs for any trips farther than the bathroom.

Activists have been going hungry in an effort to end the genocide in Gaza since October 7, 2023. As early as November of that year, hunger strikers protested for five days in front of the White House to demand a permanent ceasefire. That December, a coalition of writers and artists announced a weekly sunrise-to-sunset fast. In spring 2024, dozens of students at universities across the US and abroad launched hunger strikes as part of the broader encampment movement. Even Pope Francis, before his death, called for a day of fasting for peace in Gaza.

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

Exact approaches to fasting have varied, from Ramadan-style daytime fasts to calorie restrictions to single-day fasts. JVP Chicago’s indefinite strike was announced in the broader context of a rolling “Stop Starving Gaza” fast organized by other JVP chapters across the country, in which members take turns going without food.

In electing to protest through restricting or refusing food, activists are continuing a long tradition of political hunger strikes. Palestinians imprisoned in Israel have engaged in hunger strikes since at least 1968, with thousands starving themselves to demand better conditions and an end to arbitrary detention and the occupation.

Though fasting has a much longer and more religious history than hunger strikes, said historian Nayan Shah, the two strategies have a lot in common. “Both protest fasting and hunger striking use time as leverage,” Shah said. “How far can I go? How far can I endure? How much will I have to suffer for you to act?” In publicizing the obvious and visceral destruction of their own bodies, he said, protesters draw attention to the bodies of Palestinians who are enduring similarly preventable suffering.

As the genocide has ground on, however, the media’s attention has drifted—an existential problem for fasters and hunger strikers, whose success depends in many ways on their ability to garner public sympathy for their cause. Despite their 40-day commitment, Ferner said, the Veterans for Peace group has struggled to win the attention of major news organizations.

It has found some high-profile allies, though, including Myles, who decided to join the final two weeks of the Veterans for Peace fast after visiting the activists at their United Nations outpost. Myles has mostly stuck to the 250-calorie limit, subsisting on bits of egg and a lot of lettuce. “In some ways, I can’t help thinking that it’s just this handful of old people across from the UN,” Myles admitted. “Who’s gonna pay attention to that?”

But they’d been at a loss about what to do—as an activist, as a poet, as a person—and the fast seemed like a simple, feasible gesture. “I’m really moved by exactly what it is,” Myles said. “It’s just beautiful to do the right thing and to do it consistently, and to make it known.”

Shah sometimes gets questions about whether fasting and hunger striking have the same urgent power they once did. But he said seeing people do something so extreme to shake up the status quo still draws attention. “The question is whether they can get people to listen and make change,” he said.

For Bohrer, the JVP Chicago hunger striker, the most powerful sensation—more powerful than weakness and illness—was the awareness of how much easier they have it than any person in Gaza. “I am not caring for children,” they said. “I am not walking for miles a day to try to access food or clean water. I am not recovering from a surgery I have undergone without anesthesia. I am not at risk of developing cholera.”

Bohrer referred to pikuach nefesh, the Jewish idea that for the sake of saving a human life, all other responsibilities are suspended. “I feel a deep, intense, overwhelming conviction to that principle,” they said. “I won’t speak for the other hunger strikers, but there is nothing that I would not do to stop this genocide.”

On the Fourth of July, Bohrer, a fellow hunger striker, and six other JVP activists were arrested by representatives of the Department of Homeland Security and expelled from Senator Tammy Duckworth’s Chicago office after requesting an in-person meeting. Afterward, the remaining hunger strikers decided to stop their fast.

Before that happened, though, Alaa, a Palestinian mother living in Gaza, wrote them a letter. “To link your body with the body of a mother like me, who doesn’t know if she’ll be able to feed her children tomorrow, is a declaration that our lives still matter,” she said. “From the heart of this catastrophe, I say: we see you, we feel you, and your actions reach us even when the borders remain closed.”

More from The Nation

Brazilians held a lot of hope for democracy after the military dictatorship. But the past 40 years have proved that democracy comes at a great cost to those most marginalized.

Nicole Froio

A guide to fielding even the most ridiculous anti-Palestinian smears.

Mohammed El-Kurd

The NATO secretary general had one mission: Keep Trump happy. And to keep Trump happy, you sacrifice your dignity and play the vassal.

Carol Schaeffer

After 50 years of struggle, Chagossians won a major victory over the most powerful governments in the world.

David Vine

For many ardent evangelicals and Christian nationalists, a military confrontation with Iran is the fulfillment of a biblical prophecy.

Chris Lehmann

America cannot afford another endless war in the Middle East.

Rep. Ro Khanna

Felecia Phillips Ollie DD (h.c.) is the inspiring leader and founder of The Equality Network LLC (TEN). With a background in coaching, travel, and a career in news, Felecia brings a unique perspective to promoting diversity and inclusion. Holding a Bachelor’s Degree in English/Communications, she is passionate about creating a more inclusive future. From graduating from Mississippi Valley State University to leading initiatives like the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, Felecia is dedicated to making a positive impact. Join her journey on our blog as she shares insights and leads the charge for equity through The Equality Network.