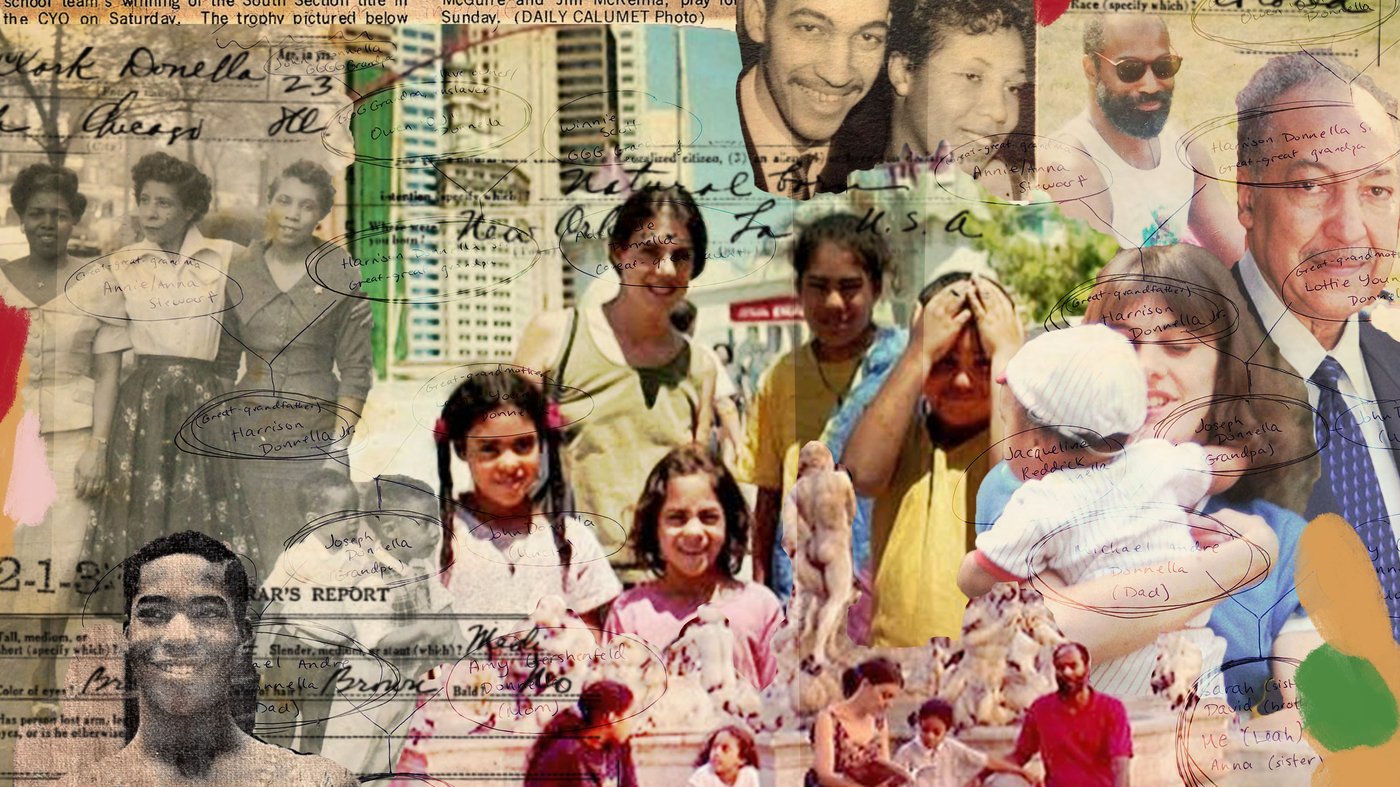

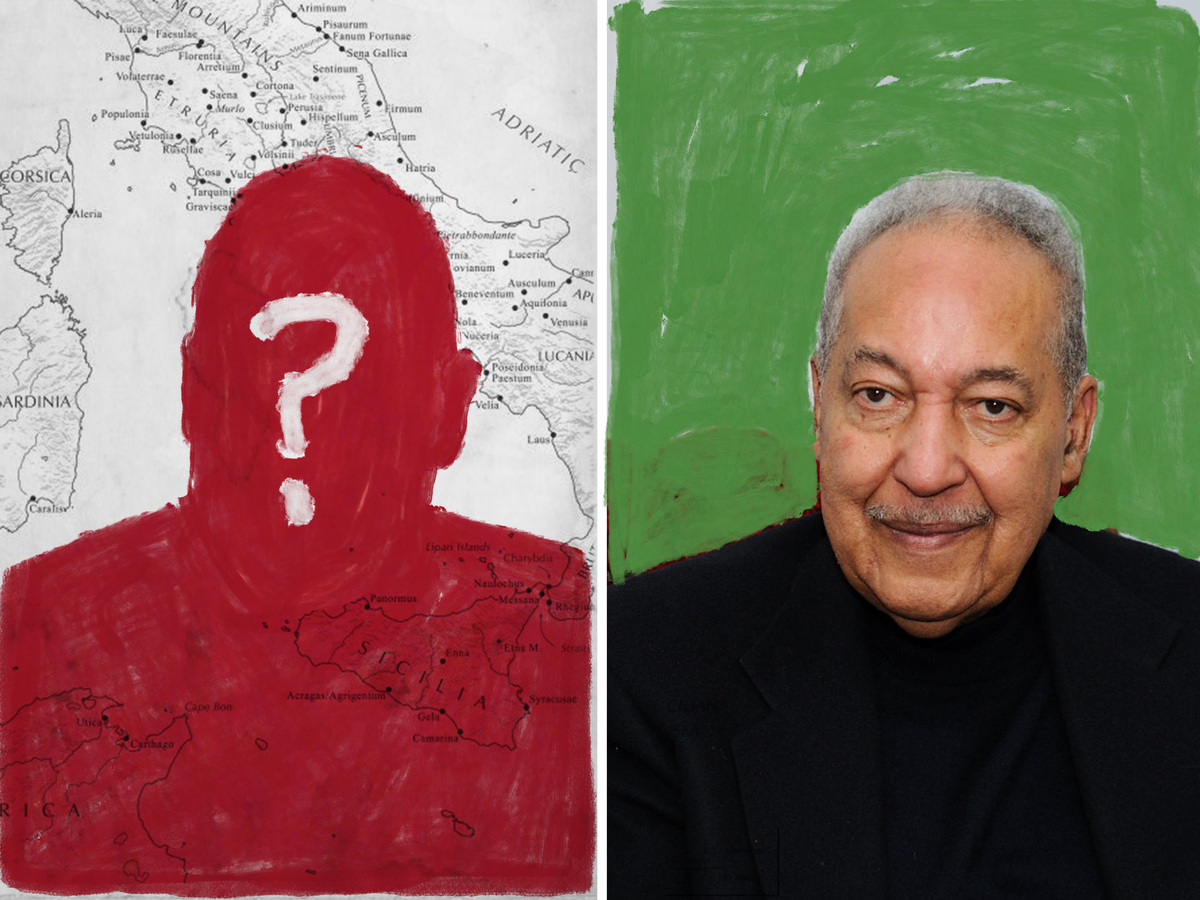

In my mind, it started out as a love story. My great-grandparents met in 1920s New Orleans, at the height of the Jazz Age. Lottie Young, was a black woman from Louisiana. Harrison Donnella was an Italian man — an immigrant from Sicily, as the story goes. My family never knew much about their courtship, so throughout my life I made up details as necessary: the two of them meeting up at dance halls, strolling along the Mississippi, sharing a beignet.

Of course, as with any epic love story, there was a problem. Interracial marriage was illegal at that time in Louisiana, so as long as they stayed in New Orleans, they couldn’t be together. So, as I pictured it, one night Lottie and Harrison stole off and made their way to Chicago. In Chicago, they started a new life. They got married, had two kids (my great-uncle, John, and my grandfather, Joseph,) and could finally live together in peace. Happily ever after.

But over the years, something a little strange happened. On some official documents, my white, Italian great-grandfather started to be referred to as “colored,” or Black. Then again, that made a sort of sense, too. Even though interracial marriage was technically legal in Illinois at that time, it was uncommon and not particularly sanctioned. So it would have been no huge surprise for a man from Southern Italy to start blending into blackness. He had a black family, lived in a black neighborhood, and sent his kids to black schools. And besides, black people come in all shades and appearances. In Chicago, at the turn of the 20th century, an Italian man could easily become black. So Harrison did. That’s how the story goes.

Rather, that’s how the story went. Until recently.

***

Every family has a myth — in some cases, an entire mythology — about where they came from and who they are. And there are a lot of reasons people tell these stories. Sometimes it’s because they genuinely don’t know the truth, so they exaggerate, or make something up. Sometimes it’s to make your family seem like they were part of an important historical event. Sometimes it’s to skirt around a shameful history. And other times, it’s to hide something that is too painful to talk about.

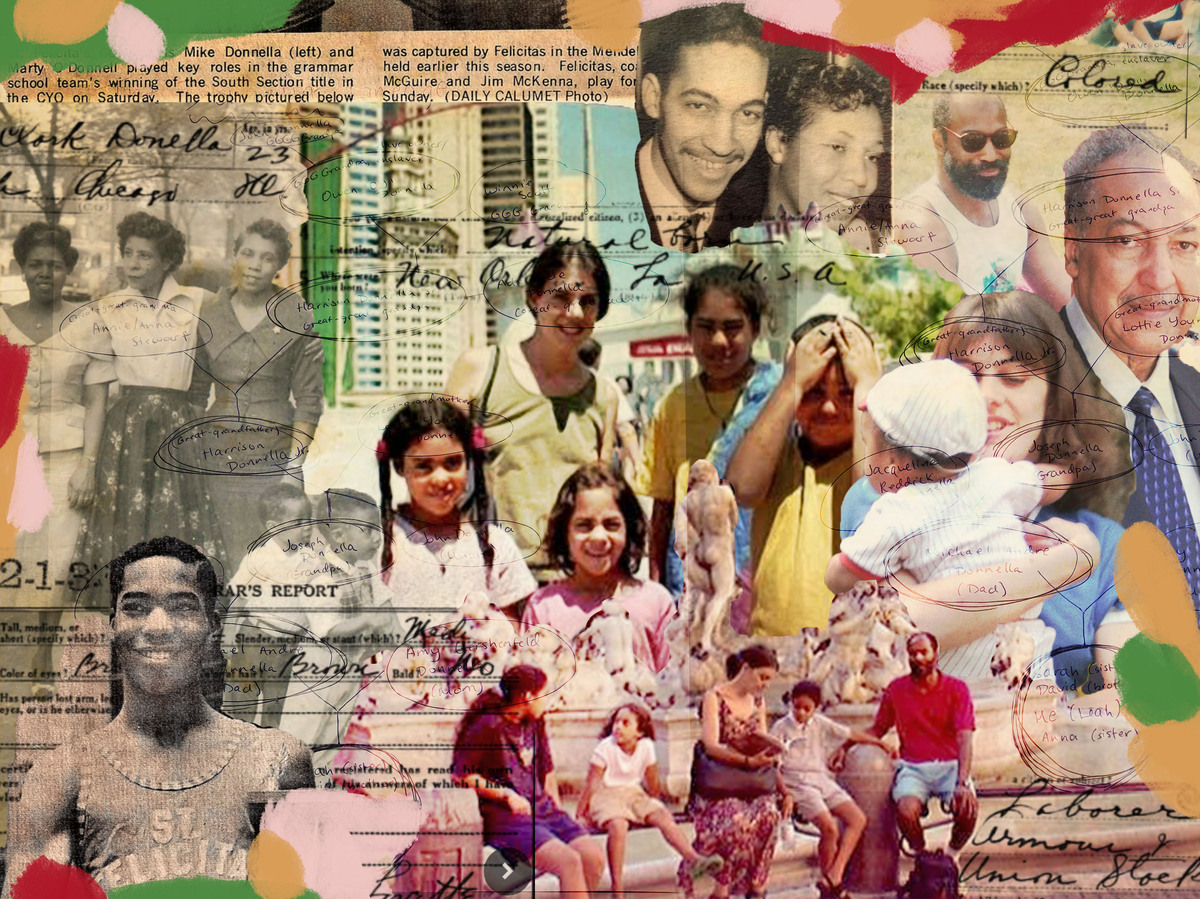

I wasn’t sure why this particular myth — the myth of my great-grandparents — had developed. But I knew it was a myth. My dad, Michael Donnella, discovered some holes in the story as a young man, when he went to New Orleans on a work trip, back in the ’70s. In his spare time, he decided to go to the public library, to see if he could find any information about his grandparents. One of the things he found was a birth certificate for Harrison. An American birth certificate. When he kept looking, he found information for Harrison’s parents. They were both American, too.

Turns out, Harrison wasn’t an immigrant from Italy. Wasn’t the child of Italians. If he had any Italian heritage at all, it would have been several generations out.

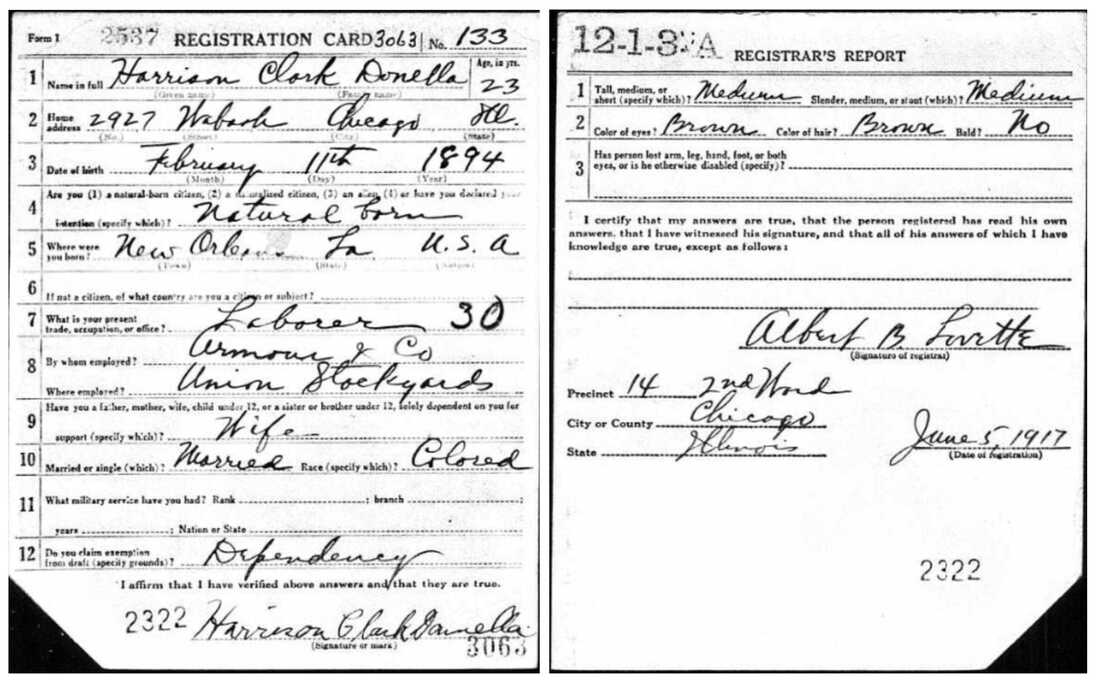

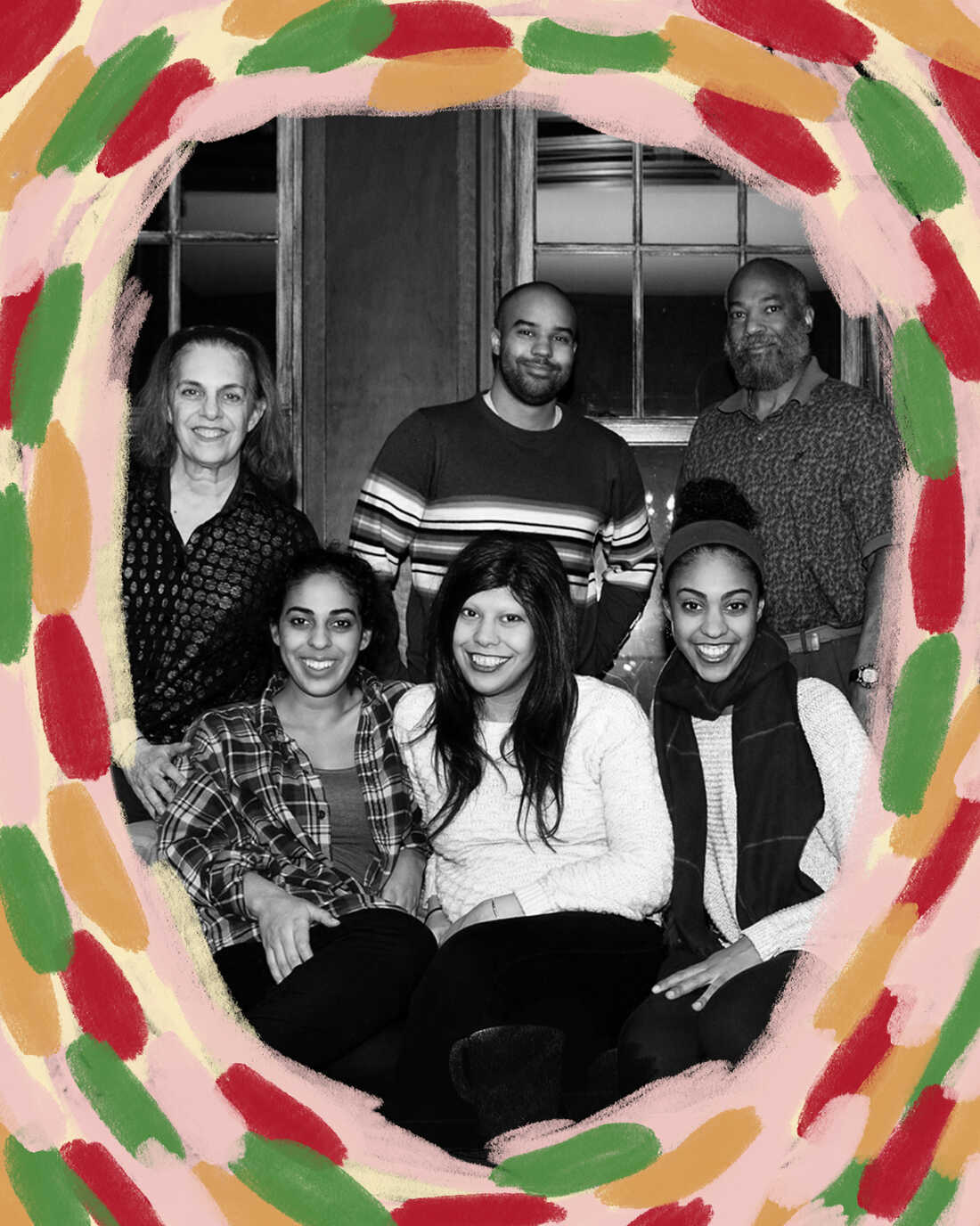

Joseph Donnella, the author’s grandfather.

LA Johnson

So about a year ago, my dad and I decided to dig into the myth a little deeper. To find out the truth, once and for all: Was Harrison Donnella a light-skinned black man, passing as Italian? Was he a white man, assumed to be black? Was the confusion about his identity imposed by other people? Or was there something about his past that he was trying to hide?

This search was important to me because, as a Black woman, I know that so much about my ancestry can never be known. My dad’s side of the family is descended from enslaved people. I’ve always known that in a vague sort of way, in the back of my mind. We come from Mississippi, Texas, Georgia, Louisiana. But there are so many things I don’t know.

Black Americans descended from slaves aren’t supposed to have a history. We’re not even supposed to exist, really. I will likely never know which parts of Africa my ancestors were taken from. I won’t speak the languages they spoke. I won’t know what those languages are. But some accident of history gave me a last name that’s actually pretty uncommon — one that I could use to track down a small part of my family’s history.

So, with those questions in mind, my dad and I headed for New Orleans. There, we strolled along the Mississippi, ate beignets, and tracked down everything we could about Harrison, Lottie, and our ancestors.

The answers we found stretch all the way back to the antebellum South And they completely blew up everything that I, and my dad, and my family, believed about who we are.

To hear the rest of Leah’s story, listen to this week’s episode of the Code Switch podcast. It was produced with help from NPR’s Story Lab.

Felecia Phillips Ollie DD (h.c.) is the inspiring leader and founder of The Equality Network LLC (TEN). With a background in coaching, travel, and a career in news, Felecia brings a unique perspective to promoting diversity and inclusion. Holding a Bachelor’s Degree in English/Communications, she is passionate about creating a more inclusive future. From graduating from Mississippi Valley State University to leading initiatives like the Washington State Department of Ecology’s Equal Employment Opportunity Program, Felecia is dedicated to making a positive impact. Join her journey on our blog as she shares insights and leads the charge for equity through The Equality Network.